I’ve written a bit about the carbon impact of various parts of our build in previous posts, but don’t think I’ve really talked about the net zero carbon ambition as a whole.

At the start of this build journey, can’t say I knew too much about the carbon impact of buildings. I certainly hadn’t heard the terms ‘operational’ or ’embodied’ carbon. Now, two years or so on, I understand much more about what these mean, and they’ve also become much more commonly discussed. Two big boosts in my education have come through a short online course in zero carbon construction by UWE and then through my involvement in 2021 in the zero carbon ‘COP26 House‘ project, designed by our architect, Peter Smith, and built in Glasgow for the two weeks of COP.

Here are some of the things I’ve learned:

- measuring carbon impact, especially of buildings, is incredibly complex! Almost the more I have learnt, the more complicated it has become. That said, things are improving all the time, in particular with the release of a framework definition of net zero carbon buildings in April last year by the UK Green Building Council.

Necessarily, behind the whole measurement system sit a whole load of assumptions – some of which seem more logical than others. One of the (on the face of it) more absurd ones (which I have to admit I haven’t checked whether it’s still in the framework definition) is that the life span of a timber framed building was initially classified to be only 60 years, compared to substantially longer life span of a concrete building. This has the unfortunate consequence that concrete ‘beats’ timber buildings in some environmental impact calculations, which seems fairly ludicrous given its massive environmental impact.* To make it worse, as part of this assumption, at the end of that 60 years, the wood will simply be burnt, releasing all the sequestered carbon back into the atmosphere. I’m sure we’ve all been in ancient timber-framed buildings that have been standing perfectly well for hundreds of years. And the idea that at the end of the house’s life, nothing would be salvaged and reused, seems slightly odd – especially when houses like ours have been deliberately constructed (with screws rather than nails) precisely so that it can be taken apart more easily at the end of its life, whenever it comes.

*Concrete accounts for 8% of global carbon emissions – which to put in context, if it was a country, it would be the 3rd largest emitter after China and US

- a precise definition of what ‘net zero’ is for an individual self-build project seems virtually impossible – the whole concept of ‘net zero’ is to reduce carbon emitted (across the full lifecycle) of all the products and processes involved in constructing and operating the building ‘as much as you possibly can’, and then offset what you can’t avoid through an accredited scheme.

There are increasingly robust definitions and models for measuring carbon in buildings, and for housing developers or large commercial constructions, I’d like to think it now works pretty well. At an individual, unique, self-built house level, the whole premise of ‘net carbon’ is less straightforward and potentially open to interpretation. Take the house we’re building, the fact that we’re building it in the first place: is it really ‘necessary’? (That said, if we personally weren’t building a house on our plot, I’m absolutely sure that someone else would be, so we’re probably ok to start from the premise that a house will be built.)

Then there’s the ‘as far as possible’ point, where do you draw the line on this for a one-off project? If an extremely low carbon product is twice as expensive as a standard product, who takes that judgement call if you can’t afford the low carbon product, that you have ‘done what you can’? Or if the builders choose to drive to site in two vans when they could have come in one. Or you choose to use a new Spanish roof slate rather than re-used ones from Scotland. And so the list goes on.

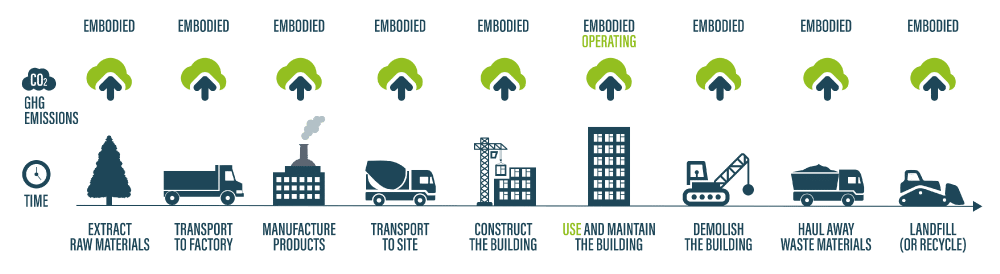

- the importance of embodied carbon – compared to when we started our build, there are now increasingly frequent conversation about energy and carbon in buildings that are being had both in the construction industry and especially in the media. However, the majority of the time they are only referring to operational energy – especially since the energy crisis. Operational energy is the amount of energy that is used once the house is built: to heat the space and water, light it, cook and cool food etc. And unfortunately, whilst it’s of course important, operational energy – especially in modern, well-insulated homes – only accounts for a small proportion of the total carbon of a building. The majority is within the structure itself, both the initial building and maintenance. Too often we see new builds on property programmes, with presenters extolling the virtues of this ‘eco’ building, and it’s a building made entirely of concrete and steel…. the most carbon intensive of building materials.

Embodied vs Operating Carbon:

- Wider impacts – it’s really important to look at the wider environmental and social impacts of all materials. It’s not just about carbon.

Here’s one example: glass, and its main component, sand. Globally, according to one statistic I came across, we are mining twice as much sand annually than can be replenished by natural geological processes. And a slightly mind-blowing statistic: 85% of all mining in the world today is for sand. In our quest for lots of light in our buildings, and windows seemingly becoming bigger and bigger, plus all the glass that is needed for electronic devices, the environmental impact of glazing doesn’t seem to be something that’s particularly considered, at least in anything I’ve come across. It’s just ‘something that we need’ and certainly for glass in windows, we don’t generally know the manufacturers and how they operate. I just looked up global glass manufacturers, and the Beijing Glass Group control a massive 2/3 share of the total global market. (If you’re interested to read more on the sand mining issue, this article gives a good overview).

So where does this leave us in our ambition to be building a so-called ‘net zero carbon house’? Relative to the rest of the house building market, I think we can be pretty proud of our low carbon credentials. Our PH15 timber frame kit, supplied by Passivhaus Homes, has been officially calculated to be Net Zero – and that includes the slab (although not the high carbon cost of transporting a lot of tonnes of type 1 aggregate that went underneath it). Once we got beyond ‘kit’ phase, obviously there are a whole lot of materials we’ve used, but in absolute volume terms they are relatively small compared to the main building structure.

Most importantly, for every item that’s been used in the house, a conscious decision has been made to select it – for example:

- our lighting from Orluna is fully circular

- our Herschel infrared heating panels are fully repairable and 97% recyclable (they’re working on the other 3%)

- for our ceiling paint we had no choice but to use fire resistant, less environmentally sound Thermaguard paint, but when we have the choice, we’ve opted for totally plant based Edward Bulmer paints

- our four sinks/basins (two bathrooms, utility room and kitchen) are all purchased from Facebook Marketplace, as are the two mixer taps for the kitchen and utility room, all shower fittings and basin taps – all either second hand or left over from other projects, and too late to return to retailer

- our solid oak door kitchen cabinets also came from Facebook Marketplace (£200 plus a bit of transport cost, compared with a £4000 quote from Howdens).

It absolutely has not been perfect, but I think I could comfortably defend virtually all our choices (from both carbon and indeed cost perspectives), and we will look for a suitable ‘off-setting’ project to invest in at the end, once I’ve totted everything up (likely involving trees).

Note: if you’re interested in calculating your personal carbon footprint, check out Giki Zero, or for more information on all things ‘green building’, UK Green Building Council is a good place to start.

Source of images: Skanska, McCownGordon