From the moment we started looking for a plot, we were always keen to build some sort of ‘eco’ house, but I’m not sure we’d thought – or knew – very much more than that at the start.

As we started discussing the house build with our architect, Peter Smith, someone mentioned the Passivhaus concept to us – the leading international low energy, design standard. At that point as we found out a little bit about it – like many people – we thought that perhaps we could just use some of the principles, but we didn’t need to go the whole way. But the more we learnt, the more we realised that building and certifying to Passivhaus standard was in fact the only way we felt we could build totally responsibly, and significantly guarantee the performance of the house that was built. It was quite some journey to get our heads round it though.

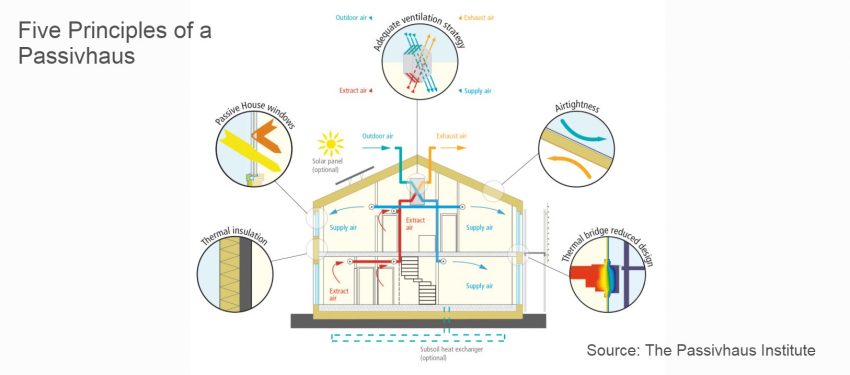

Professor Dr Wolfgang Feist, Director of the Passive House Institute in Germany, describes the standard:

“The heat losses of the building are reduced so much that it hardly needs any heating at all. Passive heat sources like the sun, human occupants, household appliances and the heat from the extract air cover a large part of the heating demand. The remaining heat can be provided by the supply air if the maximum heating load is less than 10W per square metre of living space. If such supply-air heating suffices as the only heat source, we call the building a Passivhaus.”

There are plenty of well established myths about Passivhaus, and prejudices against. The most common ones:

- “You can’t open the windows” – basically just totally untrue, and opening windows is in fact an essential part of the ventilation strategy in the UK.

- “You can’t build nice looking houses- they’re all boxes with no windows” – this was probably a view that we held (appreciating that beauty is of course in the eye of the beholder!) Ultimately Passivhaus is a standard NOT a design, and it’s down to the imagination of architects to build beautiful Passivhaus buildings. The fact that more and more UK architects – like our own, Peter Smith, are also training as Passivhaus Designers means that the diversity – and beauty – of Passivhaus buildings will increase. We certainly have no intention of building an ugly house!

- “The ventilation system is too noisy” – like many things in life, if you don’t get someone who knows how to design and commission a good system, it won’t work optimally. Those systems, incorporating a high quality product, that are designed and commissioned correctly are incredibly quiet.

- “They’re too expensive” – any ‘bespoke’ house is expensive, and any building system unfamiliar to builders and architects will almost certainly cost you more. But you need to consider the full life cycle cost of a Passivhaus building, not just the very immediate cost to construct. The cost of heating the house will be only 10% of the cost of a conventional house in the UK, and the ‘comfort’ provided by the clean air being circulated makes for a healthier environment to live in – eg no damp or condensation to deal with. The fact that the Passivhaus standard is increasingly being used for social housing speaks volumes. If the standard is built into designs from the start, there is no reason why building to Passivhaus standard needs to cost very much more. And this is certainly the case if you take into account operating costs and – increasingly – the need to account for carbon impact.

The building performance gap

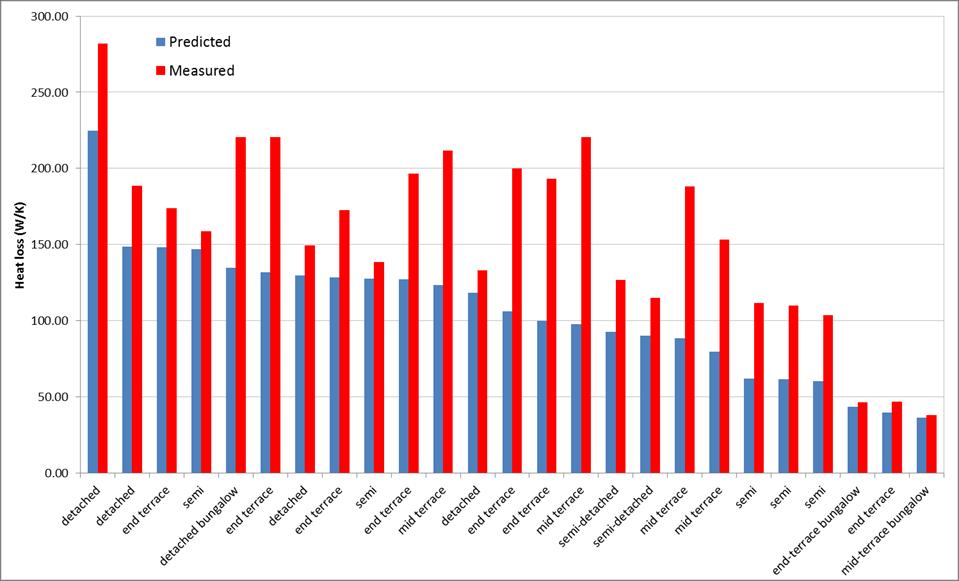

It was perhaps this chart below which had the biggest impact on us in our decision to go for Passivhaus certification. None of us would think of buying a car without having a multi-year guarantee, or indeed any product that we buy if it doesn’t perform exactly as we expected we would return it. Yet with housing – the most expensive purchase most of us ever make – whilst a ‘standard’ is set for the quality of the build in planning applications and building control make routine checks, buildings are generally not tested once construction is finished to ensure they perform in line with the specification. This article by Elrond Burrell from 2015 outlines the main issues – and points out a study that found that UK non-domestic builds typically use around 200% more energy than predicted, and another study found that houses had between 40% and 120% more heat loss than predicted. Given that buildings are responsible for around 40% of all carbon dioxide emissions, this performance gap has significant implications.

As I said, initially we thought we would just build to the Passivhaus standard, but not bother with certification, it costs another amount of money after all to go through the hoops. However, we realised quite quickly that given how the British construction industry currently works, going through these additional hoops was our only guarantee that what had been drawn was what would be built. To our builder: if you say you can build to this standard, you should be prepared to have it tested. And relative to the whole cost of the build, certification is actually a very small amount to pay for this certainty.

Challenges along the way

There were a few crunch moments along the way, as we had to change our perceptions of what we wanted in the house – things that Peter (architect), Steve and I had ‘assumed’ but were then told, quite firmly, by our initial Passivhaus consultant, Es Tresidder., that we really needed to think again. The two particularly memorable and lengthy discussions were around windows and wood burning stoves.

On windows, being a house with lots of natural light was a number one priority for us, and with a view as spectacular as ours, we wanted to be looking out at it. So when it was suggested that we take out some of the windows, this felt like a big deal. However, we’ve learnt the need to balance:

- ensure that rooms don’t overheat (this is a bigger problem in modern houses than being under-heated)

- that the sun streaming through the windows doesn’t actually make it too uncomfortable to sit in the room

- use windows to frame views

- and that (unfortunately) in the Highlands, windows on the north side of the house really aren’t great for thermal efficiency!

So we ‘sacrificed’ a few unnecessary windows and skylights, made the glazing more efficient by having larger, single panes, and (slightly reluctantly) gave up second windows on the north facing walls in the utility room and two bathrooms. The result is we still have an extremely good ratio of glazing:room area, have improved our energy efficiency considerably, will have much more comfortable rooms to sit in without too much glare from the sun, AND saved ourselves a lot of money in windows. And just to reassure: our views are all to the East, South and West, so those north facing windows we sacrificed doesn’t mean we’ve compromised on any views.

The wood burning stove was a slightly more difficult one. It’s currently hard to imagine a house in the Highlands without a fire or wood burning stove as the centre-piece of the room. Indeed most of the Roderick James Architects designs we had fallen for were very much centred around a big open sitting room complete with stylish wood burning stove. We understood the fact that a stove really wasn’t ‘necessary’ in a passivhaus early on. Lighting even the absolutely smallest stove in the middle of winter would have required us to have all the doors and windows of the house open, as the house would overheat very very quickly! (In simple numbers, our house will require only the standard Passivhaus 1.5KW to heat it – the smallest stoves are generally 4KW). So we easily accepted that the stove wasn’t necessary, but the aesthetic was still something hard to overcome.

The switch in thinking though came when we were talking to Jonathan from Passivhaus Homes: as well as being more expensive to install – as you have to draw air directly from the outside, involving challenges of ensuring it doesn’t compromise the airtightness of the building – the chimney itself would likely cause condensation issues inside the house. So this relatively expensive ‘decoration’ potentially would have a detrimental effect on the performance of our house. Decision made: no stove.

It’s been interesting to reflect on how we think about these things more than a year on from making those – at the time – difficult decisions. We no longer envisage our sitting room with the wood burning stove, and in fact with a view like we’ve got, certainly in daylight hours are happy we don’t have the visual ‘distraction’. Ensuring that the house looks ‘cosy’ during winter is something we will seek to do with furnishings – the physical ‘cosiness’ of the house will come from the fabric of the building itself. And with the move increasingly that as a country we should be switching away from this relatively polluting form of heating (more and more statistics are now coming out about the impact on public health of stoves – see this Guardian article for the discussion) – it turns out that it actually was the right way to go from an environmental impact point of view. On windows, the biggest impact is with cost: it’s likely we would have had to make changes from our original plan purely from an affordability point of view. I’ve also subsequently experienced staying in a couple of houses with large double height panels of glazing – the visual impact was absolutely spectacular, but when the sun even vaguely shone, the glare and the heat from the sun made the space quite uncomfortable pretty quickly.

For more information about Passivhaus in the UK, some initial resources:

passivhaustrust.org.uk (and their short film about what the standard delivers: https://youtu.be/hsDVIt7T7nU)

What is a Passivhaus? – a straightforward, easy to understand introduction from the Passivhaus Homes team (and I highly recommend the The Passivhaus Handbook, written by Jae Cotterell and Adam Dadeby, if you want a bit more information)